Sean Scully: Philadelphia Museum of Art

Philadelphia Museum of Art to Present Major Exhibition of Work by Abstract Painter Sean Scully

The Philadelphia Museum of Art will present a major survey of Irish-born American artist Sean Scully, featuring paintings and works on paper from the early 1970s to the present. Sean Scully: The Shape of Ideas will chart the artist’s significant contributions to the American and European history of abstract painting as it has developed over the last half-century, while emphasizing the integral relationship between Scully’s paintings, drawings, watercolors, and prints, which are rarely exhibited together. The exhibition will be on view to the public at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from April 11 to July 31, 2022.

“Sean Scully is one of the leading painters of our time,” said Timothy Rub, the George D. Widener Director and CEO of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and one of the exhibition curators. “Over the decades he has pursued a vision that has progressively opened new possibilities for abstraction, often working with deceptively simple compositional structures and on a variety of scales that range from the intimate to the monumental. He has also distinguished himself as a brilliant colorist, drawing inspiration from his immediate surroundings in places as various as Mexico, the remote islands of the Outer Hebrides, and the dense and dynamic urban fabric of New York, where he lived and worked for many years. We are pleased to share with our visitors this survey of Scully’s career, which illuminates his unique contributions to the history of Contemporary art.”

The exhibition, previously on view at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, has been expanded for the Philadelphia Museum of Art presentation to include additional paintings and works on paper, bringing together over one hundred works that reflect the many phases of Scully’s long and productive practice. Several galleries will be devoted to the artist’s virtuosic prints, featuring color lithographs, woodcuts, etchings, and aquatints. Among the highlights of this section will be a series of color aquatints from the museum’s collection, each accompanied by the verses of Spanish poet Federico García Lorca (1898–1936) along with a selection from the recently acquired portfolio Landlines and Robes (2018). The display of the artist’s prints both mirrors and offers an introduction to the galleries devoted largely to Scully’s painting practice with pastels, drawings, and watercolors integrated throughout, further emphasizing the ongoing relationship between his paintings and works on paper.

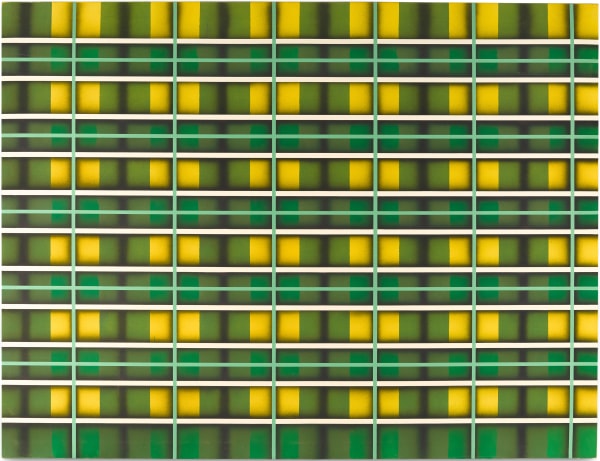

The first paintings that the visitor will encounter are important works that Scully created during a fellowship year at Harvard University in 1972–73. This experience afforded him opportunities to travel from London to New York, a major center for Minimalism and abstract painting at the time. (He would move to New York permanently in 1975.) In these works, such as Green Light (1972–73), Scully experimented with the grid, using tape and spray paint to layer the canvas and create an optically vibrant painting composed of vertical and horizontal stripes. On display nearby is Inset #2 (1973), an early example of the artist’s interest in creating a “painting within a painting,” or what Scully terms an “inset,” which remains a hallmark motif within his practice.

An adjacent gallery will be devoted to the complex multi-paneled works that Scully began to make in the early 1980s, a compositional format that would occupy the artist’s attention throughout the remainder of that decade. In these paintings, he combined panels of contrasting colors and formats into large and increasingly complex compositions, each structured by his signature “stripe.” Notable among these is Backs and Fronts(1981), an 8 x 20-foot work comprised of twelve attached canvases, which drew considerable notice when first exhibited at PS1 (now, MoMA PS1) in 1982.

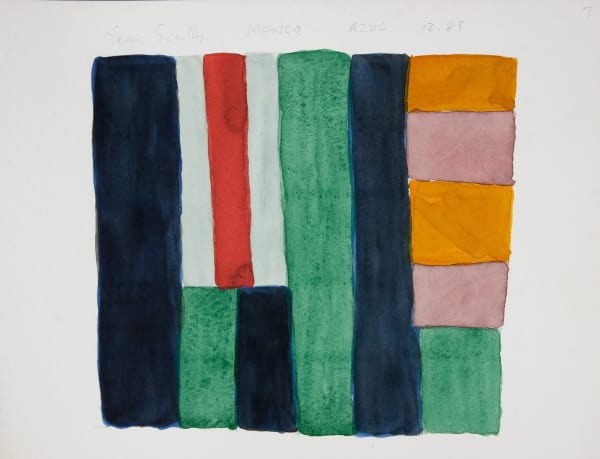

The next large gallery will feature selections from a series of pivotal works produced during the artist’s residency at the Edward Albee Foundation in Montauk, New York, in 1982. These small paintings were made using scraps of wood that Scully found in Albee’s former barn, which doubled as Scully’s studio. He then pieced the scraps together to create sculptural compositions in relief, which are represented in the exhibition through works like Swan Island, Ridge, Bonin, and Elder all from 1982. Together, these paintings reflect a turning point in the artist’s use of scale as his work became increasingly architectural. This new direction was solidified by a group of monumental paintings, among them Heart of Darkness (1982), a colossal three-panel work in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as The Fall (1983)—from the museum’s own collection. Around this same time, Scully also made the first of several trips to Mexico where he found inspiration in its architecture, its light, and its saturated colors. These travels spurred him to begin to explore watercolor as a medium, as seen in Mexico Azul 12.83 (1983).

In the late 1980s, Scully extended his experimentation with the stripe, using it in combination with compositional structures such as the checkerboard and the inset. These ideas were given form in some of the artist’s most expressive paintings, among them Pale Fire (1988), A Bedroom in Venice (1988) and Union Yellow (1994). In them, and in many other works of this period, we can trace Scully’s development as a gifted colorist.

Another gallery will feature his best-known series, collectively titled Wall of Light, which Scully began working on in earnest in 1998. Many of these works were made in response to a particular location, sensation, or memory. Their richly painted surfaces, composed in a quilted pattern of vertical and horizontal blocks (Scully calls them “bricks”), are evocative of, as the title of the series suggests, walls of stone that are paradoxically, as Scully has put it, “inhabited by light.” A selection of these paintings will be seen together with works on paper including pastels and watercolors from the same series, foregrounding the artist’s facility with working across different scales and mediums.

These Wall of Light paintings led to the development of Scully’s other, closely related compositional formats, chief among them the paintings of the Doric series, which will occupy another spacious gallery. Scully created this series as an homage to the heritage of ancient Greece, reflecting ideas of strength, resilience, and stability. Painted on aluminum, these works are more austere in their palette, which is predominantly grey and black, and more sonorous in their visual rhythms.

A final gallery will focus on the work that Scully has made during the past decade, most prominently a series titled Landlines. These large gestural paintings are made up of thick horizontal bands of color that harken back to the elegant and spare canvases that Scully produced after he came to New York in 1975. At the same time, the Landlines are among the most freely painted and unabashedly romantic works Scully has ever created. Considered together, they reflect the artist’s continuing belief in the expressive potential of abstraction and his ability to register a precise tone or mood through color. The exhibition concludes with several recent works, among them Black Blue Window (2021), a work dominated by a gaping black square that reflects Scully’s personal response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Marla Price, Director of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, and contributor to the exhibition’s catalogue, notes that the artist’s work, as it has evolved over the course of more than five decades, remains intimately connected: “Scully has spoken of his career as a ‘rolling cannibalization,’ in which he scavenges his own work and that of others to expand, develop, and move forward. The systematic elements in his early works have never really disappeared as he continues to explore different combinations of building units or motifs and then pair them with emotion and content.”

Exhibition co-curator Amanda Sroka, Associate Curator of Contemporary Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, adds: “In this exhibition, by integrating paintings and works on paper, we can understand and appreciate – in new and meaningful ways – Scully’s relationship to scale, materials, and color and the complementary roles that each have played in both the trajectory of his artistic development and in affirming his place within the Western art historical canon.”